It's Sunday, May 17 and I'm again on the trail of my notorious American ancestor, Henry Meiggs. Mike and I have flown into Palo Alto for a few days for Mike's work with ONE (U2's first US stop on the Innocence & Experience tour is San Jose), my research and (by good fortune) a chance to see our Stanford Law School daughter Gina.

Traces of Meiggs are everywhere in northern California: after a dim sum lunch with Gina and friends, we locate a street in Cupertino named 'Meiggs Lane'. It's in a quiet residential area of modest ranch houses, but since Cupertino boasts the headquarters of Apple Inc. $1.5m will barely get you through the door. It's worse in Stanford's Palo Alto, where a grandson of Meiggs lived long before the town became the capital of Silicon Valley.

But Palo Alto, for the visitor, is seductive: the majestic Stanford campus, the manicured residential neighborhoods fragrant with spring blossom, the abundant produce of the farmers' market, and the neat main street. And the beloved Philz coffee shop - pourover has replaced espresso here.

On Monday, I drive across the bay to spend the afternoon in the Bancroft Library of UC Berkeley.

In stark contrast to Palo Alto, downtown Berkeley, just outside the gates of Stanford's great rival, seems to have changed little since my last visit 25 years ago. I must be missing something. The campus itself is handsome but slightly shabby - a symptom, no doubt, of public funding constraints. But it is a joyous day, with several schools celebrating graduations. Before the library opens, I ride the elevator to the top of the campanile for a misty view of San Francisco Bay, and hear the noontime ringing of the famous bells.

My primary goal at the Bancroft Library is to read a letter that Henry Meiggs wrote to Nicholas Luning, a prominent San Francisco banker, in 1855, a year after his flight from California. I have requested the file in advance, and helpful archivists produce this and other materials. The letter is written in Meiggs' flowery script on light blue paper with a watermark of a railroad engine on each sheet - a signifier of Meiggs' new line of business in Chile. The original is quite hard to decipher, with his writing crawling around the margins to fit the last few (crucial) sentences into four flimsy sheets. But luckily a book dealer, from whom the library acquired the letter in 1987, has supplied a faithful typewritten transcript.

The letter to Luning is an attempt by the fugitive Meiggs to justify his situation and get some clarity on the charges against him and the debts he owed. We do not know if it was ever answered. I'll try to unravel its significance when I look more closely at Meiggs' business dealings.

Among other materials, I am able to view an early panorama of San Francisco Bay that shows Meiggs Wharf with the sparsely developed hills of North Beach in the background. This snapshot shows just a portion of the framed watercolor, which is about 36" x 12".

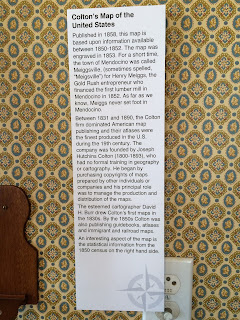

I drive back to Palo Alto through heavy traffic, and cross the Dumbarton bridge, looking forward to escaping the crowded Bay area for twenty-four hours. On Wednesday I'm heading up Mendocino on the rugged north coast to discover why the settlement was called Meiggsville (or Meigsville) in the 1850s. It is thus denoted on a map of the United States, published in 1858 by leading mapmaker Colton, and displayed at the Kelley House Museum in Mendocino.

I set out before 8am for a drive of over 200 miles to Mendocino, where I've arranged to meet the archivist of Kelley House by 2pm. It's back across the Dumbarton bridge and on busy highways that skirt Oakland and Berkeley before crossing the San Pablo Bay from Richmond to San Rafael. I opt to turn east off the highway at the first signs for Sonoma and Napa, and enjoy a meandering drive through dairy farms, vineyards and rolling hills. I take the Old Adobe Road through the attractive town of Cotati then join Route 101, the main highway through Sonoma County, aiming for a coffee break at Healdsburg, where I arrive at 10:30.

It's great to be back in this highly livable town, the gateway to four great wine valleys. We had a wonderful time here at Thanksgiving, staying at the chic H2 hotel and enjoying many a good meal, but now I just have a half hour break at the excellent Shed market and restaurant.

Continuing north through wine country, the landscape is visibly more parched than it was in November. I decide to follow Route 101 for 70 miles north to Willits, rather than turn for the coast too soon, so that I can drive through Jackson State Forest and see the inland redwoods. It is a stunning drive as the road climbs out of pretty vineyard country to cut through much more dramatic scenery of mountains and forests. The towns are few and far between - I pass by Ukiah and then turn west at Willits. For the next hour I'm descending to the coast on an unbelievably winding road through Jackson State Forest. No overtaking here, but luckily the traffic is light. The dense forest of tall redwoods shades the road - these are the trees that brought Henry Meiggs' lumber business to the north coast.

I make it to Mendocino around 1:30pm, after a five and a half hour journey, and quickly check in to the MacCallum House Inn before walking across the street to the Kelley House. Carolyn Zeitler, the thoughtful archivist, greets me and immediately introduces me to Marty Simpson, a museum board member and local historian. (It turns out that the museum board is holding its monthly meeting that afternoon, and a succession of Mendocino history buffs stop by while I'm in the archives - it's the sort of small town with an interesting history that people have worked hard to preserve, a boon for me.)

Marty introduces me to the fabulous story of the Meiggs connection with Mendocino: I hadn't heard this before, but later read everything I can find about it - notably an excellent book by anthropologist Thomas Layton, The Voyage of the Frolic. In July 1850, a year after Meiggs had sailed into San Francisco with his first cargo of lumber, a ship called The Frolic was wrecked about five miles north of what is now Mendocino. The Frolic was a clipper built in Baltimore for the opium trade in Asia. After a few profitable years of drug-running, the clipper began to lose ground to faster steamers that had entered the China trade, and her American owners decided to exploit the Gold Rush boom instead. On June 10, 1850 The Frolic had set sail from Hong Kong to cross the Pacific, laden with merchandise including silks, china, glass and bottles of beer, that would sell for a fortune in San Francisco. But she never reached her destination: Captain Edward Faucon was a veteran sailor but unaware that the charts he had purchased in Hong Kong were woefully inaccurate with regard to the little known north coast of California. On the evening of July 25, the clipper hit unsighted rocks off Point Cabrillo and was fatally wounded. Faucon ordered his men into two lifeboats (though a few inexplicably refused to come), and made his way down the coast reaching San Francisco on August 4, just ten days later. The Daily Alta California interviewed Faucon and published the story of the shipwreck and its valuable cargo the next day.

But what Faucon did not know was that the hull of The Frolic (and the half-dozen crew still on board) had washed up in a nearby cove, lodged in shallow water easily accessible to treasure-hunters. Word of the ship's precious cargo must have spread in the city and in the spring of 1851 Henry Meiggs dispatched one of his managers, Jerome Ford, to investigate. (I am not sure why Meiggs, who always had a keen eye for a profitable opportunity, waited so many months to send Ford north.)

By the time that Ford reached the wreck, its treasure had been taken - appropriated by the crew members who had remained in the area, and by indigenous Pomo Indians. Ford observed Indian women wearing Chinese silks, it is said, and the Pomos' use of Asian artefacts was proven years later in archaeological digs. There were as yet very few Western settlers on the north coast. But Ford, who was manager of a lumber mill at Bodega Bay that Meiggs owned (having bought it from a Captain Stephen Smith) reported back to his boss on the extraordinary supply of tall trees in the area. Though Point Cabrillo was much further than Bodega Bay from the main market in San Francisco - 100 miles further north - Meiggs urgently needed to find new sources of lumber to supply the rapidly expanding city.

So Meiggs dispatched Ford again, this time to find a site for a lumber operation. Ford saw an ideal location at the future Meiggsville: a bay with a broad, flat headland above it, and a wide river estuary (the Big River) with forests coming right down to the water. It's unclear whether Meiggs himself ever journeyed to the settlement that would bear his name - accounts differ on this - but there is no doubt that he established and financed the very first lumber mill on the remote north coast. The California Lumber Manufacturing Company was incorporated in July 1852, and began operations in January 1853, with a crew of about 40 men and a sawmill that Edward Williams, another agent of Meiggs, had had shipped from back east.

It was time to go into the museum to see the map that named Meiggsville, and Marty volunteered to show it to me before his board meeting.

The Colton map that was purchased by the Kelley House is a magnificent wall map that must measure about 6 foot by 4 foot. It has a beautifully decorated border of vines. It was engraved in 1853 and published five years later. And there, the only town on the coast between Bodega and Humboldt, Meigsville is clearly marked. Colton was the major American map publisher of his day, and of course travelers relied heavily on printed maps of America's relatively unexplored territory. I later check other editions of Colton maps of the 1850s, and find that between 1852 and 1858 most show Meiggsville, before settling on the name Mendocino by 1861.

Back in the archive office, Carolyn has pulled out two bulging folders of Henry Meiggs papers. It is an unexpectedly rich collection of articles, newspaper clippings and correspondence that relate not just to the Mendocino story but to Meiggs' life as a whole. I am able to make copies of some hundred pages of documents - many that I had not found elsewhere.

When preparing for my visit, Carolyn had put me in touch with another local history expert, Katy Tahja. Katy, Mendocino Middle School's former librarian, had written a column, Henry Meiggs: hero or scoundrel, for the Mendocino Beacon in 2011, and I was intrigued to meet her. She very generously comes to the Kelley House from the Gallery Bookshop, where she now works, and takes me on a driving tour around town. She is the perfect guide: married in 1975 into a family whose roots in the region date back to 1883. She and her husband live on a family ranch deep in the hills at Comptche, where they farm trees. (On a side note, she tells me that a forest fire hit them hard about five years ago, and that the drought makes it impossible to replace the lost trees with thirsty saplings.) She gives me a great local history lesson.

Mendocino is a tiny town with a big personality - its population is just 1,000 residents, including those 'up the hill' outside the historic district where we are now. The historic town (don't say village) lies along the bluff above the bay, and consists of a unique collection of houses that are more reminiscent of Cape Cod than of California. The Kelley House is one of these original homes, as is the MacCallum House, where I'm staying.

|

| The Kelley House Museum |

|

| The MacCallum House Inn |

|

| Ford Museum model of loading ships |

As the town grew, homes and businesses spread across both sides of the street nearest to the cliff. The golden age of lumber had ended by the 1930s, when the Mendocino mill closed down and the town went into a decline. But in the late 1950s and 1960s, artists and others looking for an alternative lifestyle revived the town as an art and crafts community. New residents ran successful campaigns to preserve its land and history, including an effort to designate the headland as a state park. Now the water side of the main street, once the site of thriving commerce, is all green space.

Back in the nineteenth century, Katy tells me, Mendocino was known as 'the town you can hear before you can see' because it was powered by windmills. There are still wooden water towers everywhere because there is no mains water, only mains sewage. From the start, its population was surprisingly diverse: Portuguese (from the Azores), Chinese and Finnish people all worked here alongside Americans. For a small place, it has a lot of cemeteries, including a Chinese cemetery in the traditional location at the top of a hill. One of the most colorful buildings is this Chinese temple.

We drive by Bankers' Row, the most distinguished collection of houses, including Blair House, the fictional home to the mystery writer played by Angela Lansbury in the long-running series, Murder She Wrote. Picturesque Mendocino claims many other artistic credits, including scenes from East of Eden. It is proud to have a member-supported community library, an arts center, a theater, and (as I discovered later) an outstanding book store, the Gallery Bookshop. Not too shabby for a town of 1,000 people.

There are downsides, Katy suggests, to Mendocino's allure for the wider world: the school population is half of what it was in the 1980s, as more homes have been bought by retirees and second home owners. While property seems much cheaper than in Sonoma, let alone the Bay area, the balance is shifting and fewer home owners live in Mendocino full-time.

Katy then drives me down to the banks of the Big River, just inland from the bridge that carries Route 1 past the town. Meiggs had a second, bigger mill built here after the earliest days on the headland, and at its peak it worked around the clock. Trees were felled and logs brought down river continuously. A large Chinese community lived on the opposite bank of the river, and Chinese worked in many roles: as water boys, cooks, housekeepers, and on railroad construction. The hill above the lumber mill was known as Fury Town, and was where loggers came for R&R.

Finally, before she heads home to cook dinner, Katy takes me to a viewpoint to enjoy this panoramic view back to 'Meiggsville'.

Back at the MacCallum House Inn after a very full day, I begin to read some of the Meiggs papers over a glass of wine beside a log fire in the cozy bar and then enjoy a delicious, if overpriced, dinner in the Inn's restaurant.

It seems to be a special occasion kind of place for locals, and I overhear one elderly lady telling her companions: 'Memorial Day is coming up soon, and we're going to get slammed. Stay home and hand the town over to the tourists!'

That is the other side of present-day Mendocino: a popular destination for visitors who come for a day or stay at one of the many quaint inns. Wooden logs are salvaged now not so much for builders as for woodturners and cabinet makers, and I see some wonderful craftsmanship. The artists who gave the town a second life now market their wares to tourists, and the streets are full of craft shops.

The Inn is one of those fussy places which asks you to reserve your time for breakfast when you check in, and I duly go down at my appointed time of 8 o'clock for a decent cooked breakfast. I need to leave town by 1:30 for the long drive back to Palo Alto, and there's a lot to fit into the morning, including one unexpected bonus. Carolyn Zeitler has told me that there is another Meiggs' descendant living right in Mendocino, Charles Meiggs Bush! When I call his home, he invites me to stop by later in the morning.

After a glorious walk out to the headland and down to this small log-strewn cove (so reminiscent of Devon and Cornwall), I check out of the inn and go to visit my distant relative. Chuck Bush describes himself as fifth cousin thrice removed of the famous Henry, and has the distinction of Meiggs as a middle name. Chuck and his wife retired to Mendocino around 1990, after his career as a naval officer and corporate human resources director. Their lovely home is full of treasures from time in Asia and around the world.

Most interestingly, Chuck researched Meiggs and Mendocino history after settling here, and he gives me a copy of an invaluable monograph that he wrote for the Mendocino Historical Review in 2005, How Mendocino Evolved.

In return, I'll send him a copy of At Least We Lived: like my parents, Chuck and his wife got engaged after meeting far from home in Asia and a bare half dozen dates.

Finally, I make a quick stop at the Ford House, the historic home of Meiggs' partner, Jerome Ford. Like the Kelley House this is a small gem of a museum about the history of Mendocino's founding families and the lumber companies. The director guides me towards several terrific short books on Mendocino history. I learn more about the impact of 'Honest Harry's' flight from San Francisco: the California Lumber Manufacturing company had to close down for some months until Ford and Williams, Meiggs' former associates, managed to buy the business, pay off its debts, and run a successful operation for many more years.

Leaving Mendocino but vowing to return, I head south along the dramatic coast road, Route 1. I follow this for a hundred miles, which takes three hours, to Bodega Bay, the site of Meiggs' first mill. It's hard to exaggerate the rugged beauty of the coast in these northern reaches of California. And every time that I expect the switchbacks of Route 1 to calm down, they do quite the reverse! I could seldom stop to take photos, but was pleased to capture a couple of the lumber trucks that still ply Mendocino County, though there's now just one major lumber company.

After the wild north, it's a shock to hit the crowded roads of the Bay area, but I'm pleased to get back to Palo Alto by 7, in time for dinner with Gina and Mike at Italian favorite, Terun.